The California Cannabis industry is incredibly well documented. All products and plants are required to be recorded, traced, tested, and verified from farm to final consumer sale through the METRC track and trace software. While this massive surveillance system is poorly managed, inconsistently enforced, and incredibly costly, it does allow the State to see pretty much everything that operators do.

With this level of monitoring, you may be surprised to learn that in many cases, it’s impossible for a consumer to know who grew their weed. That’s right- THERE IS NO REQUIREMENT FOR PACKAGED CONSUMER CANNABIS TO DISPLAY THE FARM OF ORIGIN. The state that is so obsessed with tracking and labeling in the name of consumer safety and transparency fails at this one basic task.

The regulations dictate that cannabis packaging must contain the following information about the product origin:

Manufacturer name and contact information - Must be a name listed on the license certificate (either the legal business name or the registered DBA), and their phone number or website.

UID number The unique tracking number issued through the track and trace system.

Batch or Lot number

Let’s unpack how useful these pieces of information are to the average consumer:

Manufacturer Name/Contact: Confusingly, this doesn’t always mean a licensee with a Manufacturer license, since other license types like Distributors and Microbusinesses can also package, depending on the product type and their license activity. This tells you the name of the facility where the consumer ready product batch was created in METRC, but nothing else.

UID Number: This is a unique identifier of the cannabis product for sale. Each packaged unit has a different one. While this number allows easy tracking of the consumer product, it reveals nothing about where the product was grown.

Batch Or Lot Number: This is similar to the UID, except it just identifies the batch of that product, but again provides zero information on its source.

Even a retailer who has a product legally transferred to them cannot query the METRC API to recover any information about where that product came from.

How does this lack of transparency affect the industry?

Who Benefits:

Not having to add the extra information to packaging makes things easier for brands. California already requires so much info that some labels barely have room for the actual branding.

Some product types have many inputs from different farms. In the case of lower-end concentrates, one batch of cheap oil can contain weed from dozens of farms. There’s no way that can all fit on a label, and asking manufacturers to publish all these farms would be burdensome.

Not being required to show where the weed came from gives brands a lot of flexibility in their supply chain- if they started a product line with Farm A’s Gelato, then Farm A went out of business or ran out of weed, the brand could just sub in Farm B’s Gelato without having to relabel their product. Likewise, they can substitute cheaper weed in for more expensive weed if they want a higher profit margin.

This gives distributors more options to play the market with their inventory and hide who they do business with. Being able to substitute cannabis inputs in products opens up new sales opportunities. Also, this secrecy allows distributors to source and sell without farms or the competition finding out who they work with, enabling them to play different sides of the market against each other.

In the case of a recall due to contamination, the manufacturer takes all the blame, since nobody knows who the farm was. This benefits the farm by allowing them to avoid the PR fallout of the recall, which they would otherwise have been exposed to even if they were not the source of contamination.

Who Loses:

Farms that sell their product to a distributor at wholesale completely abandon their brand identity and get no credit for their hard work- the brand gets all the credit and recognition.

Farms that sell their weed to a manufacturer under the impression it will be going into a certain product have no actual proof that it gets used for that product. Their product could get put into something else, sold off, or turned into generic commodity oil, while someone else’s weed is in the jar theirs was supposed to be sold in.

Farms lack visibility on the price structure of the market and can’t see if they’re being screwed. If a distributor buys a farm’s weed for 300$ a lb, packages it, and sells the resulting products at a price equivalent to 1500$ a lb, then the farm is getting horribly ripped off, but they would never know it because they don’t know what end products their weed is in to compare the margins.

In the event of a recall due to contamination, the farm loses because they don’t know if their weed was actually in a product that was contaminated during manufacturing, and therefore can’t make an informed decision about whether to work with a certain manufacturer or not.

In the case where the farm’s weed was actually contaminated and somehow made it into manufacturing, there’s no clear indicator to the farm or other market players that their product is contaminated. Lab test errors occasionally happen and let contaminated products get to market. In a non-transparent supply chain, nobody can learn from their mistakes.

Consumers and patients have no idea who grew their weed. If a consumer finds something they really like, or a patient finds something that really helps their symptoms, they can’t reliably source it. Sure, they can buy the same name branded product, but without mandatory labeling they won’t know if the manufacturer switches whats in the jar.

Consumers lose out on the opportunity to make purchasing decisions based on who grew their weed and how. Someone might want to purchase weed from a specific region, or a certain demographic, or choose outdoor instead of indoor because they’re concerned about their carbon footprint. Obscuring the farmer makes this impossible.

Finally, retailers lose out on an opportunity to diversify their sales pitches to consumers. With little to go on other than meaningless info like strain names, “effects” descriptions, or sativa/indica/hybrid designations, retailers don’t really have much real information to sell by other than vibe, THC, and price. Most retailers aren’t even really aware of how their products were grown. Lacking any information on who grew their products robs them of a key piece of information they can use to sell: the unique story, region, values, and practices of the farmer.

So, given that the State allows manufacturers and distributors to obscure the source of their products, let’s walk through a few examples of how to attempt to find the source of your weed.

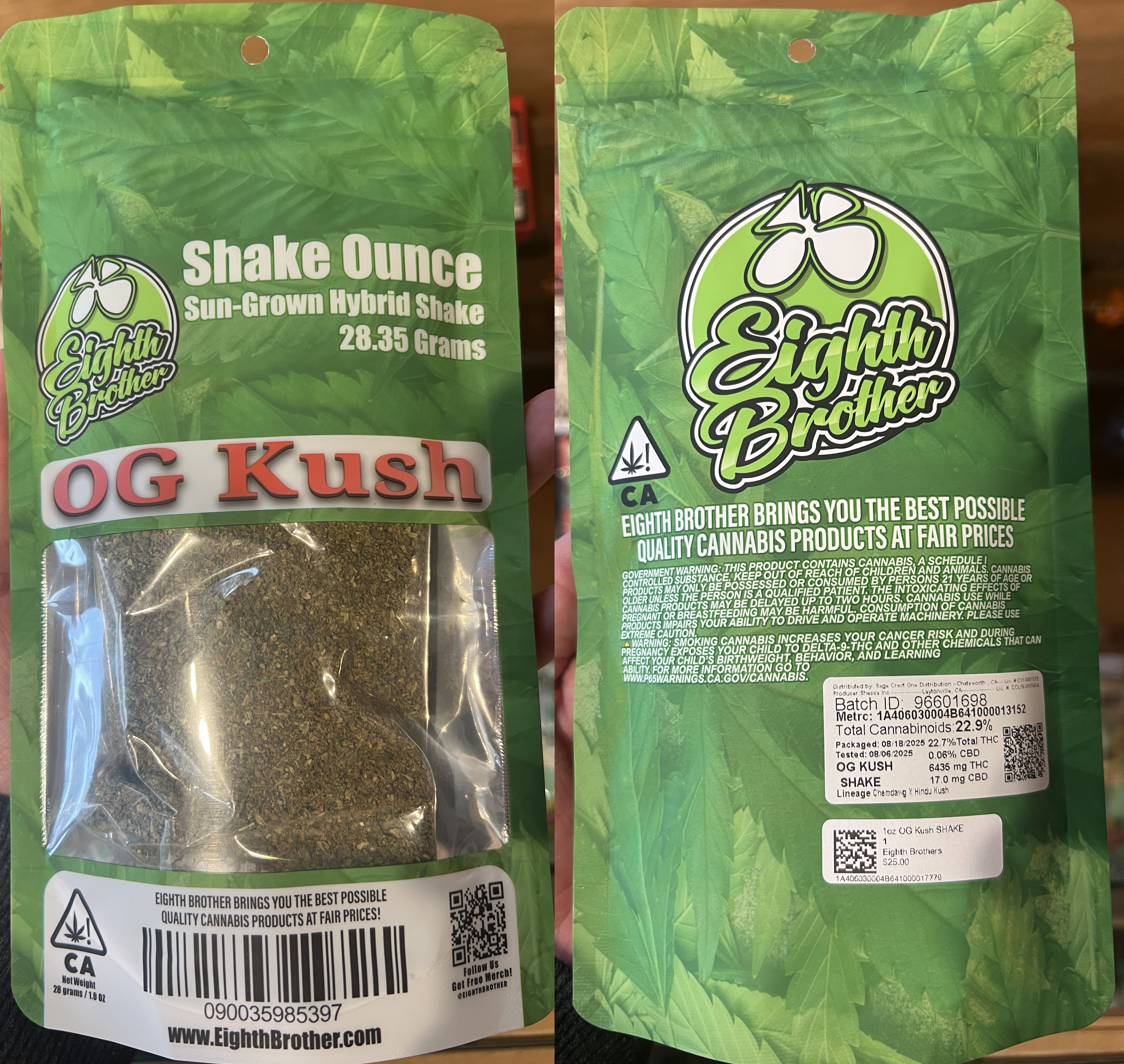

Example 1: Eighth Brother OG Kush Shake Ounce- Exceeds Expectations, Traceable!

The bag itself doesn’t contain the farm’s name, but if we look at the top of that large label, we can see written “Producer: Shessa Inc. Laytonville, CA, Lic # CCL 18-0003414. If we search this license number on the Higher Origins License Search, it reveals that this is a Small Outdoor farm in Mendocino County. We have to congratulate Eighth Brother here for clearly labeling the farm! They included extra information that they were not required to, and now we can thank the farm for their work. We can also infer a bit more about this product from the information available.

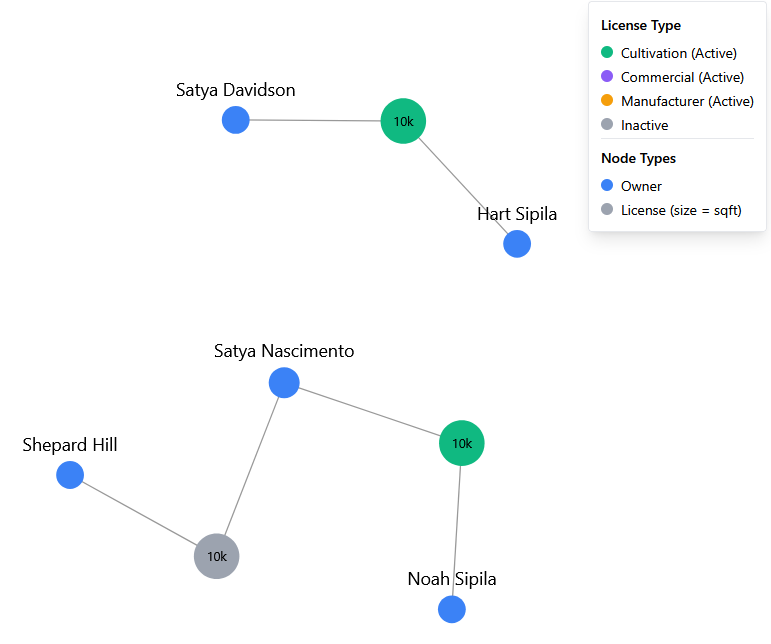

The ownership and related licenses of Shessa Inc

Based on the Packaged and Tested dates in August 2025, we can assume that this weed was actually grown in 2024. Outdoor cannabis in the Emerald Triangle usually wraps up harvest by late October, and shake is usually the last material left over after all the more desirable bud has been sold, so unless they harvested super early this is likely from last year's crop. This is not immediately obvious, since the State also doesn’t require the harvest date to be added to products.

One interesting thing about this product is that it’s listed as being distributed by Sage Crest One Distribution, aka Dog Jacket, operating out of Chatsworth, a town on the outskirts of LA. Since these products were photographed at a store on the Mendocino Coast, it means that this weed had to travel over 1,000 miles down and back the length of the State to end up in a retailer less than 50 miles from where it was grown! Unfortunately, this gives this shake a pretty big carbon footprint, offsetting some of the environmental benefits of it being sungrown.

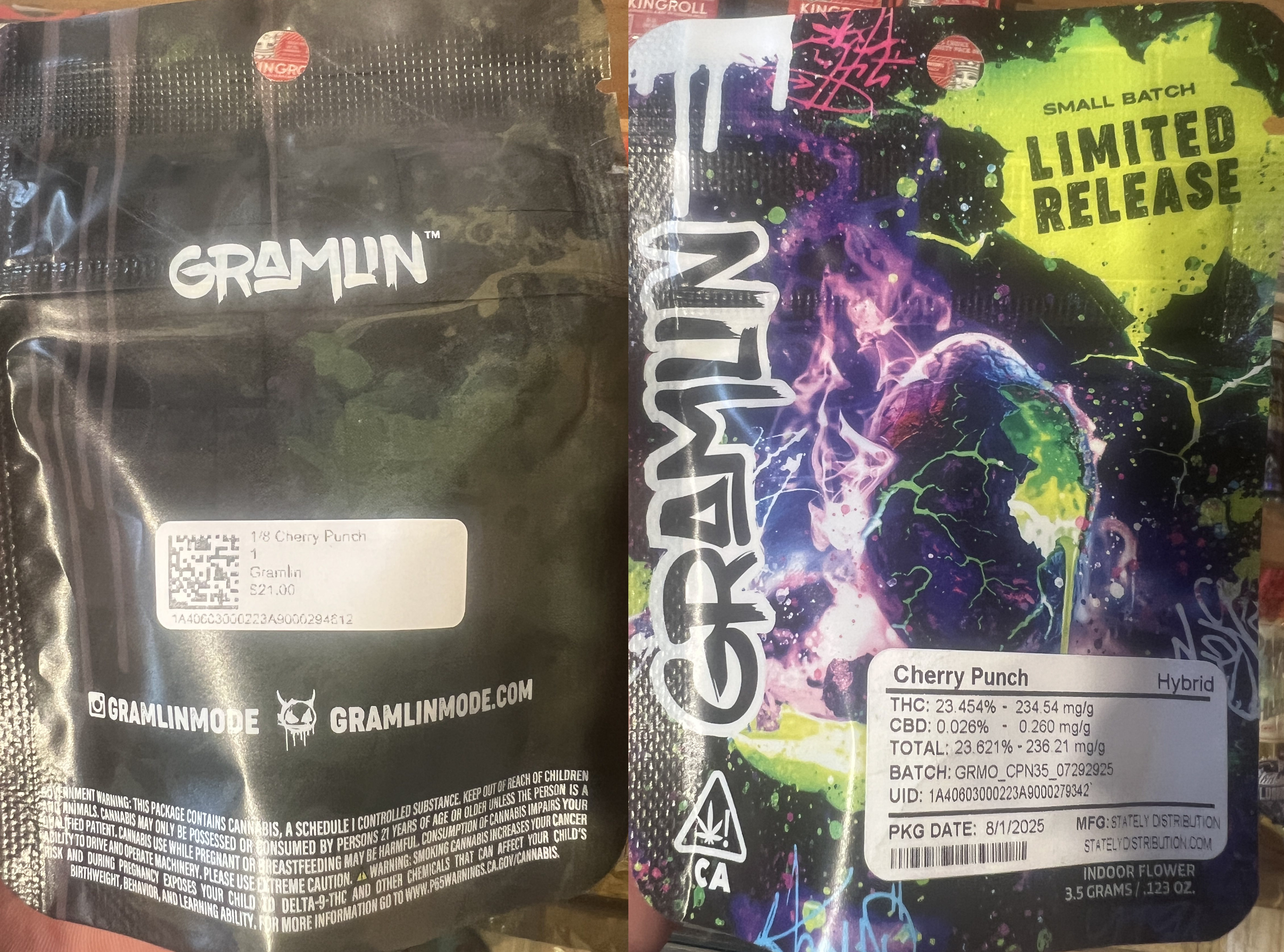

Example 2: Gramlin Limited Release Indoor Cherry Punch 8th- Typical Megafarm Antics

The packaging itself doesn’t tell us anything about who grew it. Time to research!

Let’s start with a simple Google. This reveals gramlinmode.com, which lists some flower strains, but this Cherry Punch is missing. Nowhere on the site is a farm mentioned, but they do mention in their About section that their flower is “Cultivated with care” which is nice to hear. At the bottom of the page is a license number: #C11-0001268. Let’s look that up.

Using the Higher Origins Search, we find that the number is for GF Distribution in Riverside County. This is all well and good, but it’s different from the name listed on the packaging itself, Stately Distribution. Searching that on our license search, we get… nothing, actually. There is no licensed business or DBA called Stately Distribution. That’s odd, you’d think the name on the package would correspond to a licensed entity since the regulations clearly state “Must be a name listed on the license certificate (either the legal business name or the registered DBA)”. Oh well, let’s check out that website, statelydistribution.com.

It appears that Stately is a big company that manages a ton of well known brands like Gold Flora, Aviation, Mirayo by Santana (site broken), Monogram (site broken), Caliva, Jetfuel (defunct), and of course, Gramlin. But, there’s no license number here. If we poke around the site more, there’s not much there. However, if you click the link to their Facebook, their profile lists the license number: #C11-0001268-LIC. This is the same one as listed on the Gramlin site, GF Distribution. Also, their profile states they are in Costa Mesa.

Some more Googling of Stately Distribution brings up a press release from 2023. This really brings it together. Stately was founded by Gold Flora, a multibrand company which at the time had just been acquired by The Parent Company, another huge cannabis conglomerate. Stately was founded to “provide premium service and support to the California cannabis market. Stately will operate comprehensive sales and management for the Company’s (Gold Flora’s) rapidly growing first party brands”.

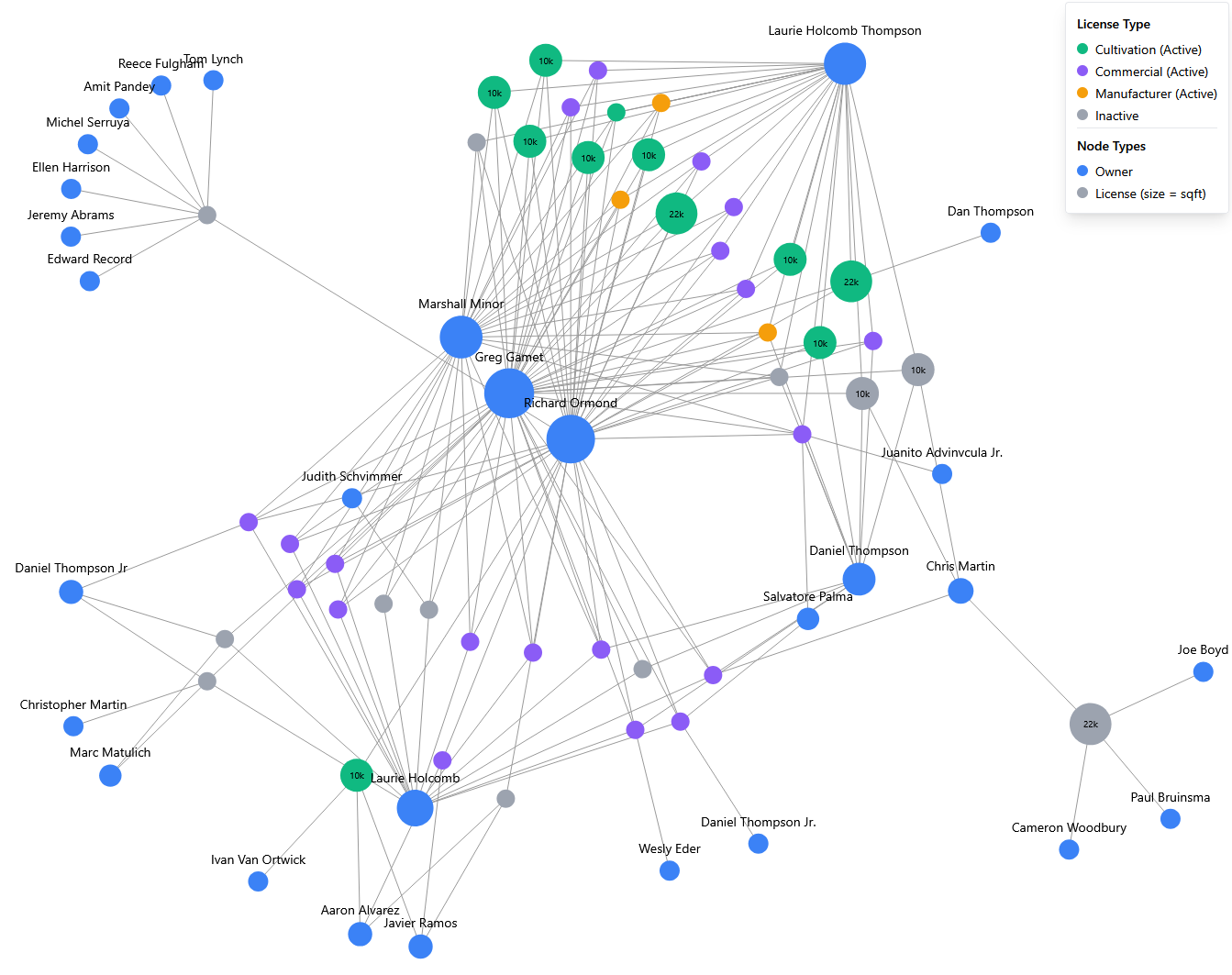

The ownership and related licenses for GF Distribution/Stately Distribution

Further down the press release, we get a clue to where this weed was grown: “Gold Flora Corporation operates an indoor cultivation canopy of approximately 72,000 square feet across three campuses, with the opportunity to expand to a further approximately 240,000 square feet. Its 200,000 square-foot cannabis campus located in Desert Hot Springs, California – that has the ability to scale to 620,000 square feet.”

So, we can assume that this indoor 8th was probably grown in one of these desert megafarms. We say probably because we can’t be sure they just bought this from any farm in the state through their distribution.

To add one more twist to the story, Gold Flora went under in March of this year, and is currently in receivership, although it will continue to operate as a going concern.

So, to sum up this story, this weed was LIKELY (but not for sure) grown in the past year in a megafarm campus in or around the SoCal deserts, owned by a conglomerate corporation that is currently being legally dissected. Then, it was packaged into this potentially non-compliantly labeled Mylar in their distribution facility alongside a huge amount of other brands.

This is a classic example of big corporate cannabis: brands and management companies nested like Russian dolls, all leading back to some huge industrial facility and sent out in cheap packaging with zero indication of where it came from, all while the company falls apart. Shame!

Example #3: West Coast Cure Orange Creamsicle Jefferey Sativa Infused Joint- What the hell?

This infused joint comes packed with different kinds of concentrates, which is a problem for figuring out where it came from. The flower, kief, terps, and diamonds may have come from different crops or even different farms. Still, let’s see what we can do here. The labels contain no extra information, so we’re really left here with nothing to go off other than the brand name, product name, and manufacturer’s name.

Let’s start with the manufacturer, Shield Management Group. A Higher Origins search reveals a distribution facility and a Manufacturer in LA, which is not surprising or helpful. Turning to Google, we find… oh boy. The entire first page of results is about a Class Action filed against Shield Management, AKA West Coast Cure, over falsified test results for failed products. There appears to be merit to at least one of these product contamination claims, as there’s also a recall for one of their products.

The ownership and related licenses for Shield Management Group

So, now we know that this brand is at least under suspicion of selling contaminated products, and has sold at least one. Knowing that, wouldn’t it really make a consumer feel a little better to know exactly what kind of farm their weed products came from? Let’s keep looking. Googling the product name gets us this listing on the West Coast Cure site, but other than claiming it’s made using “Top Shelf Buds”, there is no helpful info. Looking around the site a bit more at their About page, Flower page, and an article about the Jefferey product line, reveals no more information about where their flower comes from, other than that their “Top Shelf” is likely indoor and they “work with legacy farmers and new innovative growers.” Still no clue. Let’s go deeper.

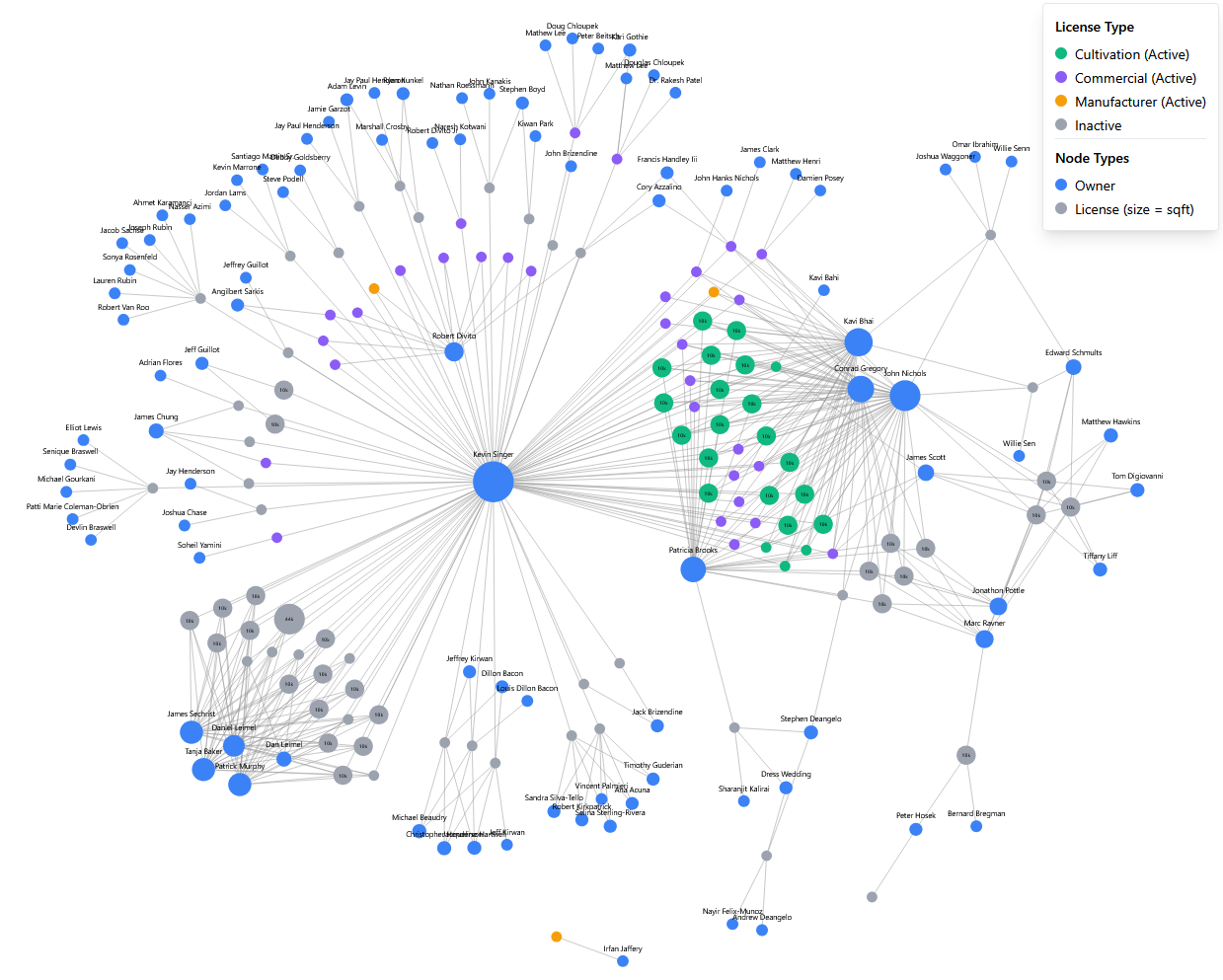

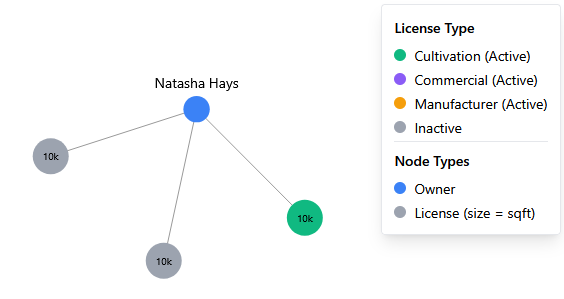

If you’re looking for farms associated with a brand, the names of the owners can be useful. California publicly releases the names of all cannabis license owners. The Higher Origins license search contains a graphical tool that shows associated owners and licenses, so we see if the same person owns multiple licenses under different businesses. In this case, both Shield licenses have the same three owners. Interestingly, one owner has two different versions of his name entered as a licensee, so he appears in the search as two different people. Searching these names lists a few more expired licenses, as well as a distributor called Trilli in Santa Cruz. Very little information pops up anywhere for Trilli, so let’s look elsewhere.

LinkedIn can be a good resource to dig through when researching companies. On their company page, you can go through the list of people who have listed WCC as their employer. Nobody there seems to have a title related to cultivation, so it’s really starting to seem that they do none of their own growing. Trilli turns up nothing on LinkedIn either. Looking up the owners likewise reveals no results.

The West Coast Cure Instagram is down, so there’s nothing to be found there. Likewise, Facebook returns no clear results, just a few trapper groups with the same name and an old profile from 2011.

So, realistically, this is a dead end. If West Coast Cure was a public company, they might have some more detailed corporate filings we could dig through, but it is privately held. We could get even more obsessive and dig into every legal filing we could find associated with the owners and main employees, hoping to find mention of a farm or name that was associated with one, but that borders on stalkerish insanity. The most we can guess is that this product may contain some kind of indoor flower, bulk bought from a farmer somewhere and packed in West Coast Cure’s facility. For a brand fighting allegations of contamination and doctoring results, you’d think they would have a greater interest in transparency.

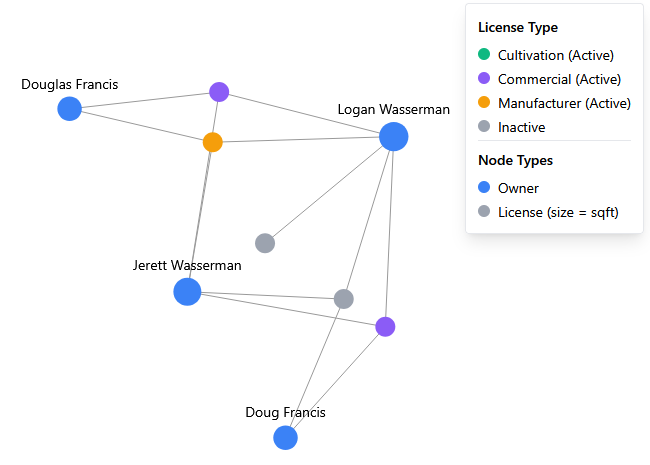

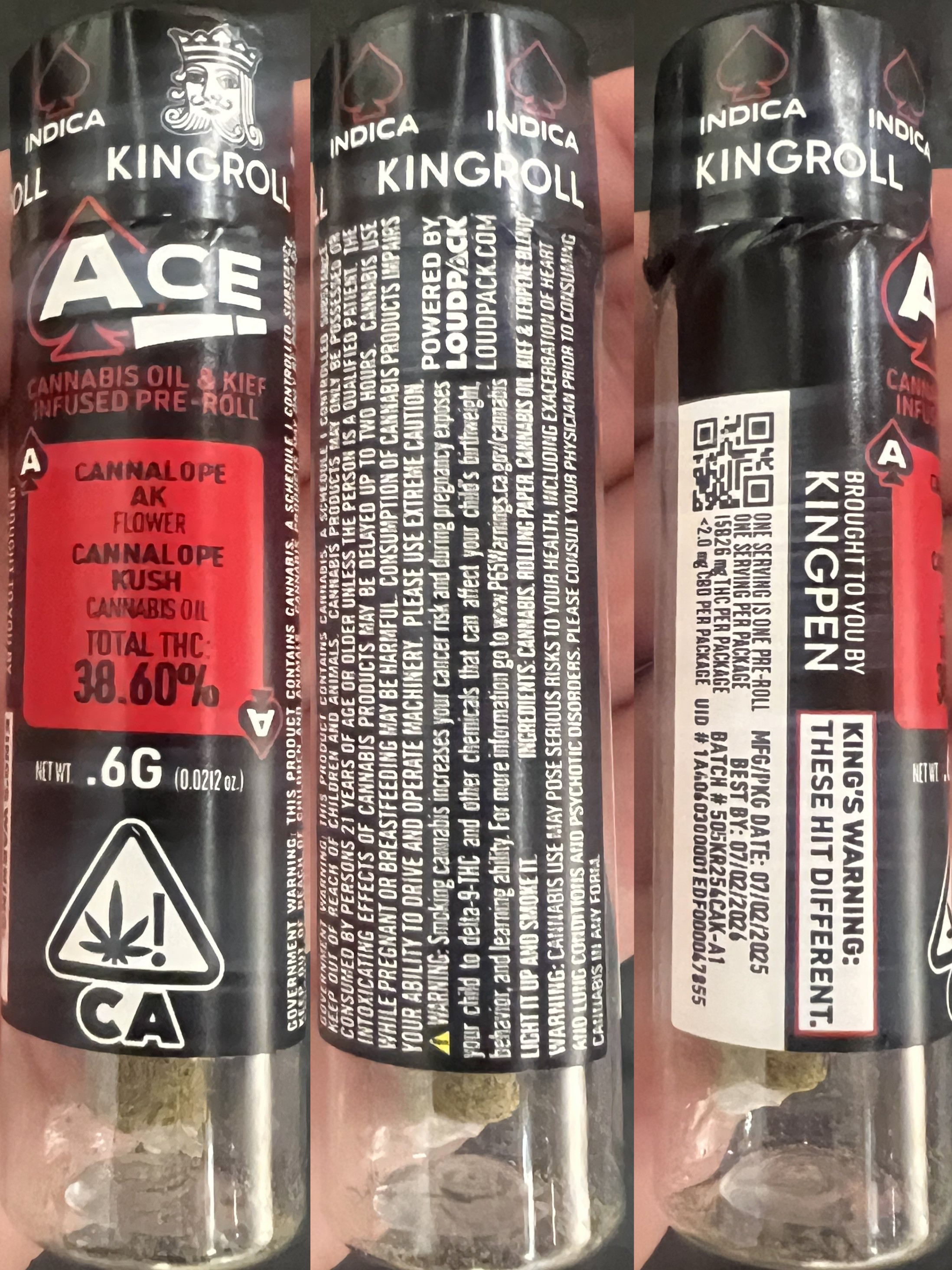

Example #4: Kingroll Ace Infused preroll, Cannalope Kush Indica: Some general info but nothing super specific

Time for another infused preroll. This guy has oil and kief added to it, so like the last product it could have been made from material sourced in many different places. Again, all we have is brand name, product name, and the name of the manufacturer, Loudpack. As before, let’s start with the manufacturer. Their website actually has a tab that takes you to a somewhat unfinished page for their farm. It looks like they grow in a large greenhouse facility, and the description of their process implies that they use the plants there for their extracts as well. That’s all the information listed there though, so we have to dig just a little more to find out more about this farm.

Using the same license owner name search method that we used on the last product, we find that the owners of Loudpack also own a large amount of farms in Monterey County under the name FlrishFarms.

Likewise, Loudpack also operates under a DBA of Greenfield Organix, a name that also returns a large amount of farms in Monterey.

The ownership and related licenses of Loudpack/Greenfield Organix/FlrishFarms

It looks like this product was grown in one of these large greenhouse facilities in Monterey County, and probably extracted and packed there as well by Loudpack. It took a little searching, but this large brand infused product was easier to track down than most, although the exact facility and license number is still elusive.

Example 5: Trailheads Premium Flower Pinnacle ¼ Oz bag: Loud and proud!

This quarter has a strong start from the beginning, with some pro-farmer language on the bag, as well as a sticker of a farm’s name, and logo, and a brand Instagram QR. Since in this case it’s clear who grew it, let’s just go straight to their website. The site explains that Trailheads is a group of farmers in Trinity county who are collaborating on this brand and are loudly pushing back against corporate influence in the cannabis industry. Checking out the Farms section, we find Haze Family Farms, who grew this product. A little bio explains that Haze Family grows outdoors in Junction City, and have been growing for over 25 years.

Searching this farm on the license search surprisingly has no results, which means that the DBA or licensed business name must be something other than Haze Family Farms. A quick Google turns up an Instagram with a ton of content about the farm. Let’s try an experiment. The owner’s names are listed on the Trailheads site and their Instagram, and one of the owners has a less common name than the other, so let’s just search that name in the license search and filter for cultivators in Trinity. And there we go, Trinity Herbal Company. This isn’t a huge problem since there is so much info on their Instagram, but if a consumer was really trying to find their license number it would be an obstacle. Also, this is the only Trailheads branded farm with this issue so it’s probably just an oversight.

The ownership and related licenses of Trinity Herbal Company/Haze Family Farms

Let’s look up the distributor, Solex Distribution. A license search reveals a distributor and manufacturer license for Solex under the DBA of The Goodfellas Group in Santa Ana, Orange County. Like the Eighth Brother shake from the first example, this product has to travel the whole length of the state to a distributor.

Overall, this brand really goes out of their way to put their farmers right on the bag and make them a central part of their message. To be clear, this is a brand run by the farms themselves, so that makes sense in comparison to a large corporate brand who views farms only as suppliers.

Here’s a list of the methods you can use to track down who grew your weed:

Step one is to just look for obvious info on the packaging, scan any codes you can see, etc.

If you’re in the store, ask the budtenders! Usually budtenders just learn about the products based on what’s written on the jar like everyone else- especially at larger corporate dispensaries. Sometimes though, often at independent stores, they might know who grew your weed.

When in doubt, Google it. Be careful with the “AI” features, they’re often wrong.

License searches like the improved Higher Origins search, or the original State search tool. These allow you to search more than just license numbers, since they also store owner names, business names, and phone numbers.

Social media like Instagram and Facebook are always worth checking but many brands put little information on there or have had their accounts removed by the platforms.

Searching companies or owners on LinkedIn can reveal connections.

If you’re tracking down a company, OpenCorporates is a good place to look for owners and filings.

Also useful is the California Business Search.

If you have a website that you think may have once held the info you're looking for but it may have since been removed, use the Archive.org Wayback Machine to look at archived versions of the site.

For larger brands or businesses that are publicly traded, Googling their name along with “shareholder statements” or “earnings” can turn up the regular reports that they are required to release, which often detail their holdings and major activities.

A lot of regional and city governments post things like building and permitting documents for cannabis projects on their websites. These are worth searching for because they often clearly state the businesses involved and the use case of whatever is being built, like cultivation or packaging. Sometimes you can find these kind of documents more easily by adding “filtype:pdf” to your search query since most of them are hosted as PDFs.

Call them! A lot of numbers for brands are dead ends, but if you’re polite and get the right person, you might get lucky. Often though they’ll just tell you that they don’t reveal that information.

Understand that it’s very possible that you simply won’t be able to find out who grew your weed. This is the system working as intended, as annoying as it is. The best thing you can do about it is to contact your representative, tell your retailer you won’t buy anonymous weed, and support the brands that have the balls to be transparent in their sourcing.

Conclusion:

We understand that this is a longer and more in depth article, but we did this on purpose to illustrate a point: consumers must often go to ridiculous effort and research to find the source of their weed, despite the cannabis industry having a ridiculous level of surveillance in the name of consumer safety. This is a thorny issue, and likely would be extremely difficult to change legislatively due to the fact that the lack of transparency favors large wealthy brands who can afford to influence officials through lobbying. Nevertheless, we feel that it is important to document.

Higher Origins is always working on ways to improve small cannabis farms access to market, emphasizing transparent cannabis supply chains. The shorter and more visible the path from farm to shelf is, the higher quality and safer the consumer’s weed will be. You can check out our offerings here. If you’re a licensed cannabis operator in California, you can sign up here for free, it just takes a couple minutes. The more brands and retailers on our platform, the more we can ease the selling and sourcing of small farm cannabis- we need your help! We’ve built this platform from the ground up in Mendocino County with a core team of two and a few collaborators, and we have no corporate overlords.

If you don’t know who grew it, DON'T SMOKE IT!

-The Higher Origins Team